Fifteen years ago, then-contributor Peter Lipson wrote a short post on this blog that I’ve reflected on many times since. Titled Your Disease, Your Fault, Peter described a central theme that runs through nearly every variant of alternative medicine: That illness is preventable, and therefore, your fault. According to this worldview, disease isn’t a product of biology, inequity, or chance. It is a failure of your personal responsibility. If you’re sick, it’s because you didn’t exercise enough, take the right supplements, avoid all the vaccines, or do the correct detox.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. doesn’t believe in germ theory. He is a proponent of miasmas, an abandoned 19th century medical idea that attributed disease to poor hygiene and inadequate ventilation. Miasma theory had moral overtones – lack of cleanliness was not only unhealthy, but a sign of failing or laziness. Under the banner of “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA), RFK Jr. is translating this ideology into policy, reshaping health care in America.

Wearables, like smart watches, are part of this movement. Once used primarily by athletes, they’ve gone mainstream, and are now tools for health “optimization”, and personal accountability. It’s an appealing idea on the surface: that wearables can reduce health care costs and help Americans better manage their own health. However, this narrative risks stigmatizing illness, distracting from science-based interventions and programs, and ultimately, undermining public health.

The old new health ethos: Illness as moral failure

As Peter Lipson pointed out so succinctly fifteen years ago, the idea that all illness is preventable isn’t new – it’s long been a cornerstone of alternative medicine. But under MAHA, this fringe, unscientific belief has moved into the mainstream. RFK Jr. and his allies are promoting a vision of health that’s not just about personal habits, but also personal virtue. If you’re sick, it’s not bad luck, or bad genes – it’s your bad choices.

MAHA seems to be reworking public health as a series of moral decisions. RFK Jr. has claimed that nearly all chronic disease is preventable through diet and lifestyle alone, and his health policy proposals emphasize individual action over broader health system actions – particularly in areas of public health. Fluoride and vaccines are out. Take care of your health by rejecting “toxins”, eating organic, and tracking your own biology.

This kind of thinking is at odds with what is known about diseases and their causes. RFK Jr. downplays or ignores the role of aging, genetics, infection, environmental exposures, and structural inequities in influencing health. He frames illness into a moral failure, something you could have avoided if only you had tried harder. MAHA and RFK Jr. offers certainty instead of acknowledging complexity (just look at his messaging about autism) and it replaces compassion and science-based medicine with judgment and increasingly, pseudoscience.

MAHA’s embrace of wearables

Wearables are a growing theme among the MAHA evangelists and appear to be a key part of the “personal accountability” strategy. The new Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, Marty Makary, spoke about them during his Senate confirmation hearing, when he suggested that wearables like glucose monitoring devices, currently prescribed mainly for people with diabetes, should be available over-the-counter. He framed them as tools that could could address growing rates of obesity, and help prevent diabetes.

Casey Means, recently nominated to be US Surgeon General, is another proponent of wearables. Her book, Good Energy: The Surprising Connection Between Metabolism and Limitless Health argues that all chronic disease is a result of “metabolic dysfunction” and is effectively under your control. It ties in with the MAHA ethos – good health is your responsibility. Means is a cofounder of the company Levels, a which aims to “Bring Biowearables into the Mainstream and Improve Metabolic Health”. In a 2024 blog post, she wrote,

A CGM [continuous glucose monitor] is a biosensor that can alert us to early dysfunction, coach us on how to eat and live in a way that promotes Good Energy in our unique bodies, and promote accountability. My belief in the potential of this technology to reduce global metabolic suffering is why I cofounded Levels, which enables access to CGMs and software to understand and interpret the data.

Is a CGM useful for those with diabetes? Absolutely. It beats repeated pinpricks and diabetic test strips. But as a lifestyle device – the evidence isn’t there yet.

A few weeks ago, RFK Jr. spoke about how wearables are a central part of his MAHA vision:

We’re about to launch the biggest advertising campaign in HHS history to encourage Americans to use wearables…It’s a way people can take control over their own health. They can take responsibility. They can see, as you know, what food is doing to their glucose levels, their heart rates, and a number of other metrics, as they eat it…We think that wearables are a key to the MAHA agenda of making America healthy again and my vision is that every American is wearing a wearable in four years.

Data-driven discipline

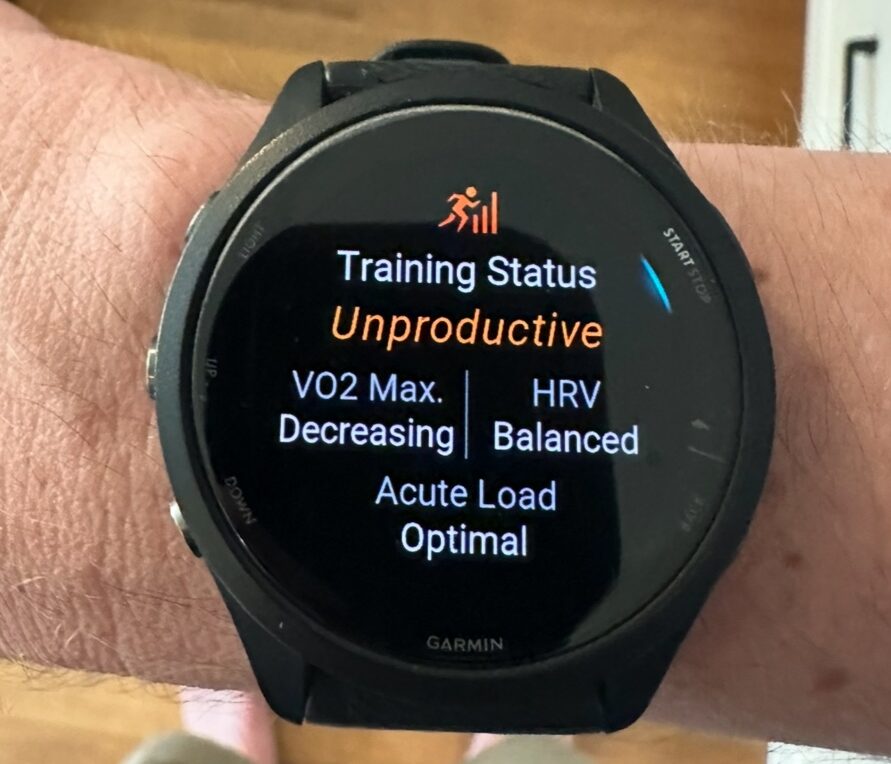

The appeal of wearables lies in the promise of control. As I wrote two weeks ago, these devices have move from simple heart rate monitoring to collecting, analyzing and reporting an enormous amount of what looks like objective data. My Garmin smartwatch offers me real-time feedback on sleep, stress, workouts, recovery, and more. Other devices, like the Apple watch can give you an ECG. If you’re using a CGM, you can monitor your blood sugar on your phone in almost real-time. In theory, this information will help users make informed decisions about their health. And there is absolutely some potential for that to happen. But in practice, it also reinforces the idea that a deviation from “optimal” health is a personal failure, and any ill health is a consequence of something you didn’t do – but should have.

Shifting the focus from what’s effective

RFK Jr.’s vision of a nation where “every American is wearing a wearable in four years” doesn’t sound metaphorical. He is framing this as a central strategy to reduce healthcare costs and chronic disease burden. Importantly, notice what’s not on the policy table: It’s not improved access to health care professionals, investments in public health, or social programs that address known contributors to suboptimal health. Instead, this initiative offloads the responsibility for health to individuals, while minimizing the systemic factors that we know have an effect on health outcomes.

Rather than investing in evidence-based public health measures, like clean water, equitable care access, vaccination campaigns, or health system improvements, the MAHA approach focuses on personal responsibility and optimization. The message is clear: if you just track enough data, you can avoid disease. And if you don’t? That’s on you.

Could it work? As I noted two weeks ago, there is limited evidence that wearables can drive meaningful improvements in health outcomes. Early data is promising, but there’s (as yet) no persuasive evidence that these devices can eliminate (or even significantly reduce) chronic disease.

Then there are equity questions. A health system reshaped around wearables assumes everyone has the time, resources and digital literacy to use these technologies effectively. It ignores the needs of people who are uninsured, underhoused, chronically ill, elderly, or disabled – many of whom already face multiple health challenges.

By tying health outcomes to individual choices and digital self-surveillance, MAHA policies risk making healthcare less equitable and overall, less effective. They promote unproven technologies that may feel personally “empowering”, while diverting attention away from public health interventions that actually work, like vaccinations, nutrition assistance, and access to primary care.

Don’t blame the ill for their illness

Wearables are not inherently harmful. l like the feedback my Garmin gives me. Used appropriately, wearables can support healthier habits, offer helpful feedback, and (as my friend with new onset atrial fibrillation discovered,) even flag early signs of illness. But MAHA is positioning wearables as tools and instruments of personal virtue, part of an ideology that sees disease as personally preventable. This is a re-imagining of public health not as a collective responsibility with a key role for government, but as a personal responsibility, with wearables giving you feedback and keeping you virtuous. In doing so, it ignores the complexity of disease, overlooks social determinants of health, and ultimately, blames the sick for being sick. Your disease, your fault.